Browser-First, Offline Data Services Demo

January 2026

In Field-Ready Emergency Ad-Hoc Networks for Real-World Deployments, we argued that most MANET systems fail for reasons unrelated to routing. Phones are locked down, users are unprepared, and designs that assume apps, special Wi-Fi modes, or prior setup collapse during outages. This post documents a working counterexample. It asks whether an unprepared person with a stock smartphone can connect to a powered-on device and exchange useful information immediately, entirely offline.

What the demo does

The system runs on a small OpenWrt-based node (Raspberry Pi 4B). On power-up, it boots a custom senzuru image from SD, expands its filesystem, and brings up a Wi-Fi access point advertising a SENZURU SSID.

Any nearby phone that joins the network is redirected automatically to a captive portal. That portal serves two browser-based services:

- a real-time chat interface

- an interactive map with pins, icons, and comments

There is no Internet access, no accounts, and no application installation. Updates appear immediately for all connected users. At this stage, this is intentionally a single-node system. There is no multi-hop routing or long-range backhaul yet. The purpose is to validate onboarding, interaction, and usefulness—the layer most systems never fully test.

Why starting with one node is sufficient

Emergency networking discussions often jump straight to topology: coverage radius, hop counts, throughput. That framing assumes the user problem is already solved. If people cannot discover a network, join it quickly, and exchange information within seconds, routing performance does not matter. A single node is enough to validate:

- zero-install access

- browser-first interaction

- offline operation

- immediate utility

Multi-node networking changes how data moves between nodes, not how people interact with a node. The phone-side experience shown here is a data-layer demo intended to run unchanged over a future multi-hop network. Later demonstrations with interconnected nodes will keep this demo intact and carry it forward as a reference service layer.

The correct mental model

Each node behaves like a pocket Wi-Fi router. Phones connect locally using ordinary Wi-Fi and remain clients at all times. They do not relay traffic or participate in a mesh.

Any long-range connectivity—sub-GHz links, Wi-Fi HaLow, wired backhaul—exists only between nodes. Phones stay local; nodes handle relaying. Treating these roles separately avoids common design errors.

What users actually see

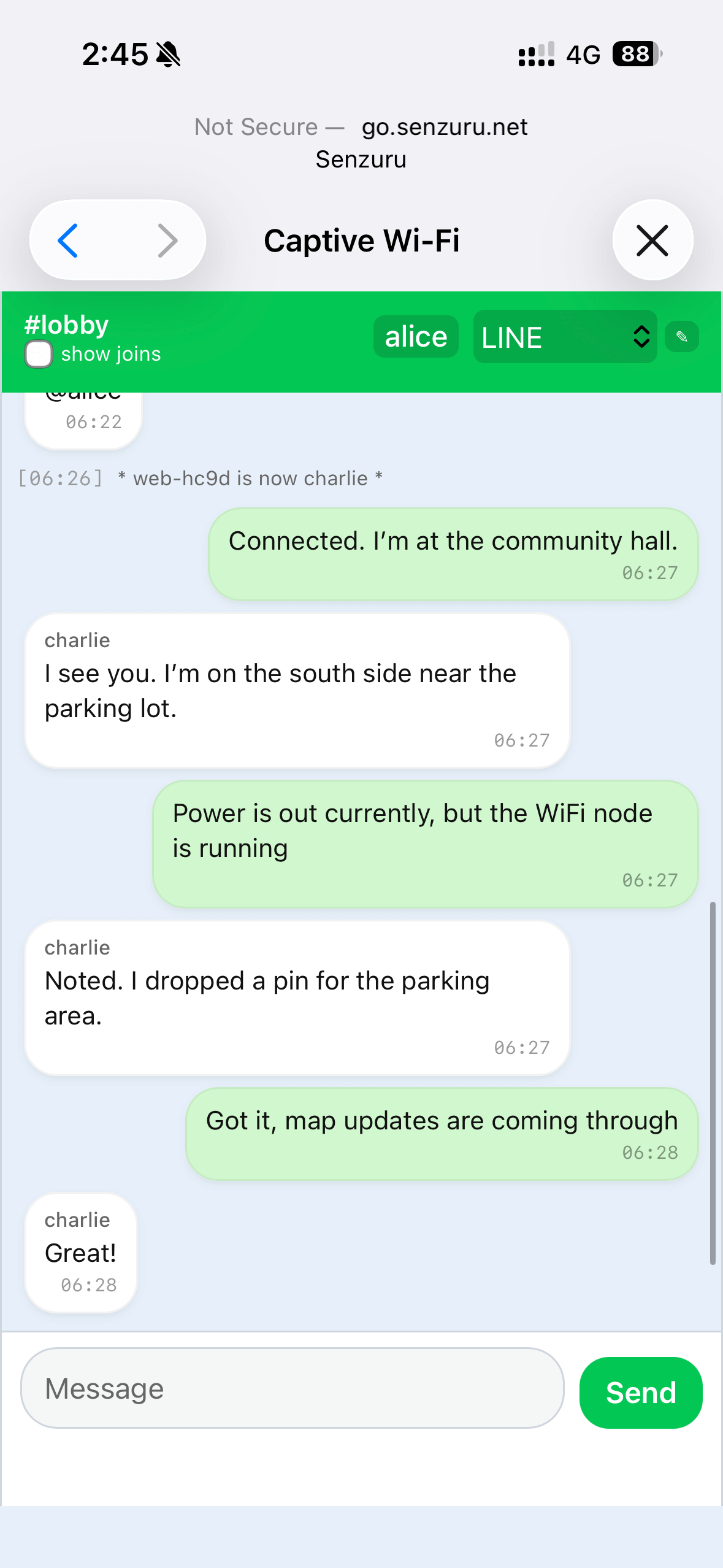

After joining the Wi-Fi network, the phone’s OS launches a captive portal automatically. The interface presents two tabs.

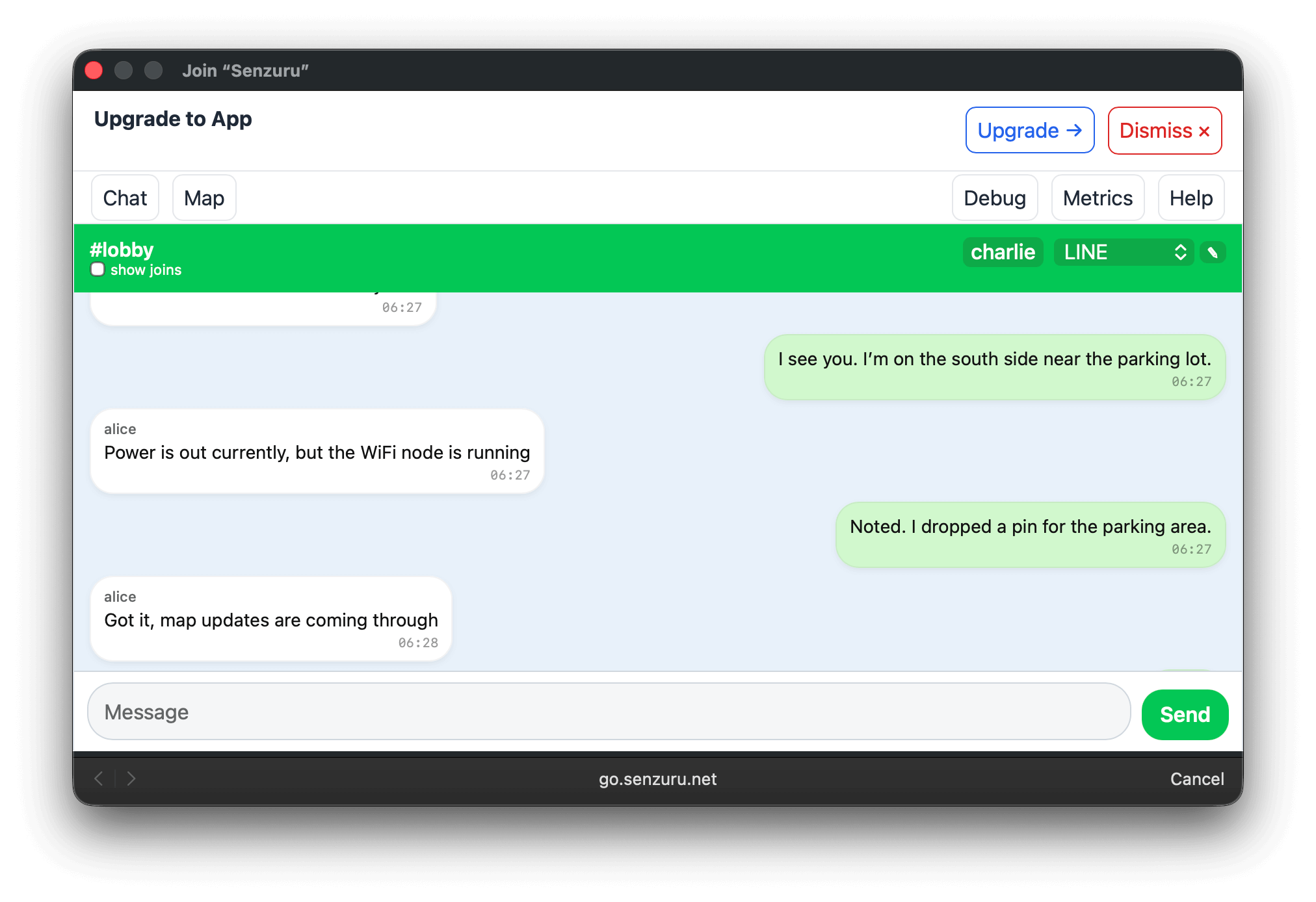

Chat: A minimal, familiar interface for short messages. Messages appear in real time to all connected users and survive reloads.

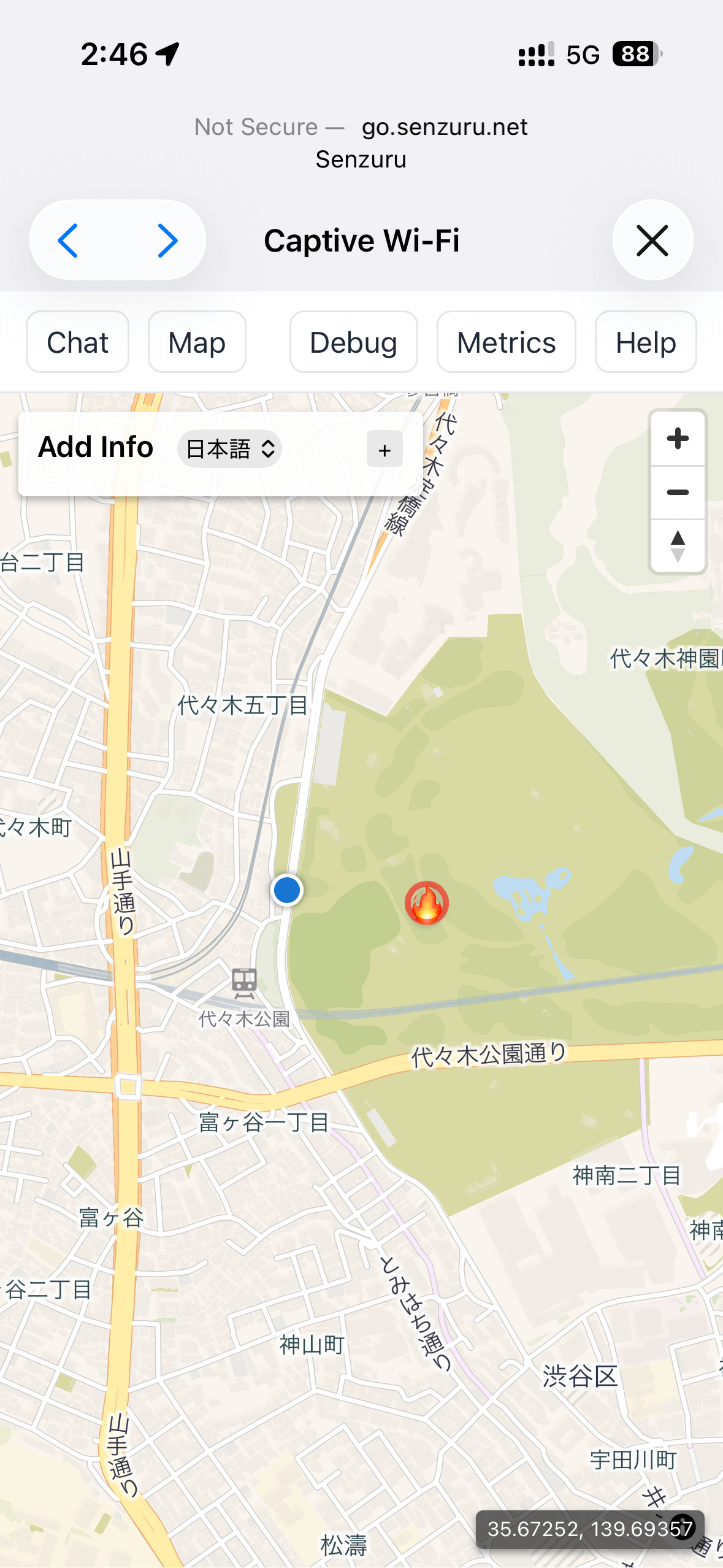

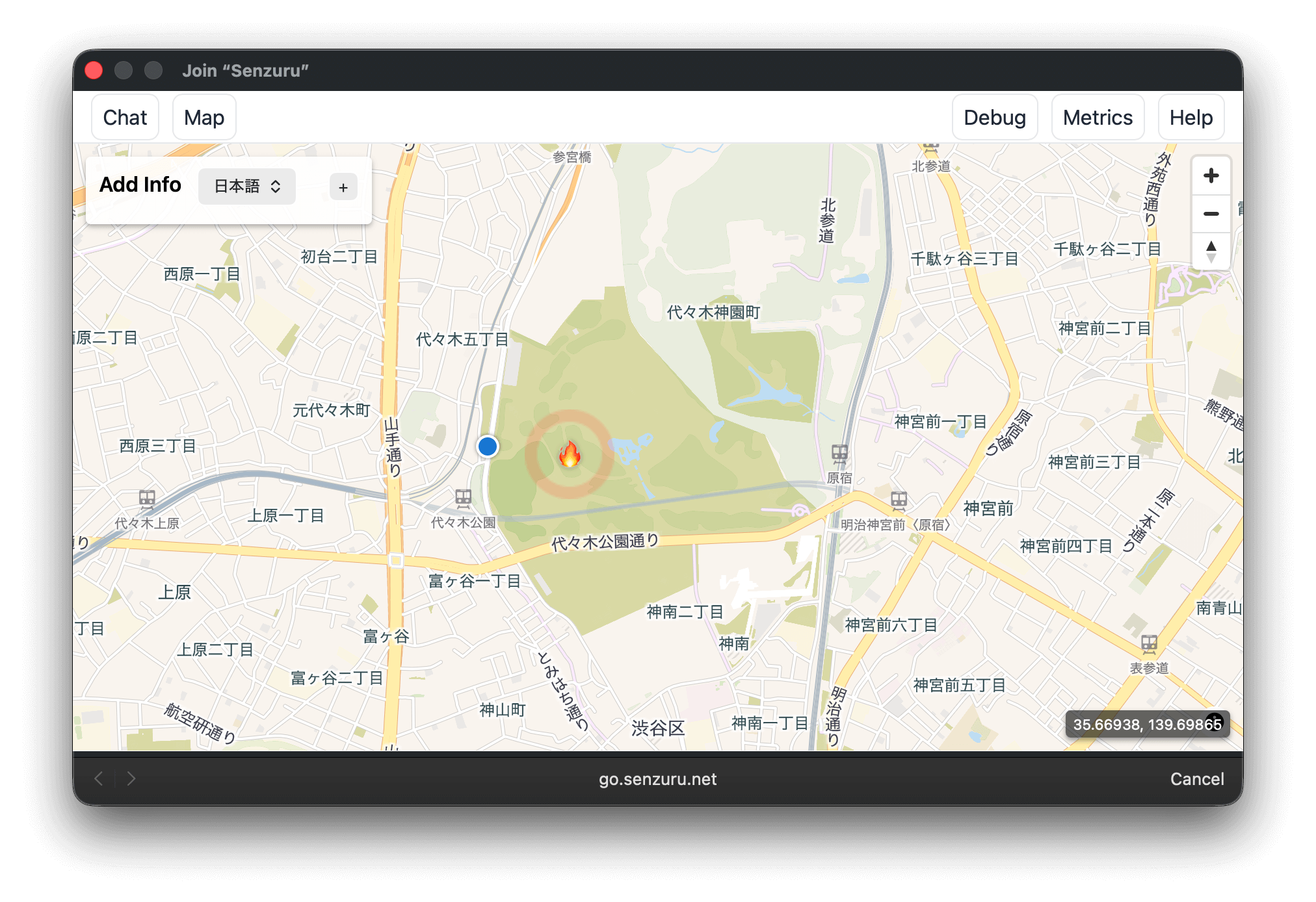

Map: A locally rendered OpenStreetMap view. Users can place pins, select icons, and attach short comments. Updates propagate immediately to other clients.

These workloads were chosen because their behavior is immediately understood under stress. They expose synchronization, update propagation, and contention without requiring explanation.

Smartphone (iOS)

Real-time chat in the captive portal.

Map view with pins and comments.

Desktop (macOS)

The same chat interface in a desktop browser.

The same map interface rendered locally.

About the data layer

Chat and maps are examples, not the system boundary. From the node’s perspective, they are simply local data services.

The underlying storage and synchronization layer is agnostic to payload type. Messages, map annotations, check-ins, or sensor readings are handled the same way. In a multi-node system, these become structured data units that can be queued, forwarded, filtered, or dropped according to policy and available capacity.

The demo shows one understandable workload, not the limits of the architecture.

Custom data layers and operator control

The services shown here are a demo workload, not a prescribed application surface. An operator deploying a real network can replace the entire data layer and service set. The node does not require chat, maps, or any specific UI. It only requires that some services be exposed locally to clients.

A deployment may include:

- pre-installed applications specific to the operator’s mission

- authenticated services gated behind credentials, certificates, or device identity

- data models and synchronization rules tailored to local policy

- non-interactive services such as sensor ingestion or message ferrying

End-user access and operator control are separated by design. The captive portal guarantees universal first contact. Administrative actions—service configuration, credential management, routing policy, data retention—are performed through operator channels and are not exposed to the public UI.

The demo shows what must work for unprepared users. It does not constrain what may exist for prepared operators.

A note on ATAK and the TAK ecosystem

The Android Team Awareness Kit (ATAK) and the broader TAK ecosystem are often cited as evidence that emergency and ad-hoc networking is already solved. They are a relevant reference point and are compatible with the approach shown here.

TAK systems assume prepared users: trained operators with pre-installed applications, managed devices, and established credentials. Within that model, TAK provides rich situational awareness and data exchange over disconnected or constrained links.

The browser-first layer demonstrated here targets first contact with unprepared devices. It provides discovery, local access, and a minimal data surface that works on any stock phone. In practice, both layers can coexist on the same node, serving different user populations without conflict.

Why browser-first holds up in practice

The demo exists to validate a claim from the earlier article:

In an outage, the captive-portal browser is the only universal application surface.

That claim holds. Every major mobile OS detects captive portals, launches a browser automatically, and permits basic interaction without user training.

Approaches that depend on pre-installed apps, background services, special Wi-Fi modes, or OS-level routing permissions remain fragile outside controlled environments. This demo works because it accepts platform constraints instead of working around them.

Captive portals as a primary interface

Captive portals are often treated as a nuisance layer. In offline systems, they are the only interaction surface that reliably exists on unprepared devices.

On a stock phone with no Internet access, this path is dependable:

- join a Wi-Fi network

- allow the OS to detect a captive portal

- interact with a local HTTP page

This flow exists because it is required for hotels, airports, and public networks. The captive browser is limited, but text input, simple UI state, and basic JavaScript work consistently.

Several familiar patterns do not survive offline conditions. HTTPS with self-signed certificates produces warnings that require deliberate user action. PWAs and service workers are gated behind HTTPS. App store installs require vendor infrastructure and connectivity.

The system therefore draws a clear line:

- Universal access: plain HTTP via captive portal, zero preparation

- Optional upgrades: trusted certificates, HTTPS, PWAs, richer UI for prepared devices

Advanced capabilities never block basic participation.

What changes when nodes connect

When nodes are later interconnected, messages and map updates may traverse hops. Latency and bandwidth constraints become visible. Policies may limit what data is forwarded.

What does not change is the phone experience. Phones still connect locally. The captive portal flow remains the same. Interfaces behave identically. Usability and deployment can be proven before radio topology enters the picture.

Closing notes

Many mesh-based networking projects disappear because they are never usable by the people they are meant to serve. This demo does not claim to solve routing, coverage, or capacity at scale, but establishes prerequisites.

Zero-install participation works. Offline services can be immediately useful. A browser-first approach survives real platform constraints. Without these properties, sophisticated networking does not matter.

Future posts will cover inter-node links and data movement. This one establishes a baseline that works before it scales.